It must be acknowledged that artists’ efforts to escape institutional constraints drive the expansion of art. Each attempt to challenge limitations, redefine art, or integrate it into life and local communities stimulates chemical interactions with audiences, though complete escape from institutional control remains impossible. Similarly, we, as part of the field, cannot escape the art system; there may exist an “external field,” but it lacks concrete verification and does not appear as a tangible entity. Actions occurring outside this external field do not affect the internal system. As art cannot exist beyond the art field, actions outside it would not constitute art. Viewers, curators, critics, and artists all exist within the art system, as institutions are embedded within ourselves and cannot be transcended (Fraser 2005). Institutionalization is therefore less a physical framework than a conceptual or ideological structure deeply rooted in the art field, determining what counts as art; in other words, art has never and cannot exist independently of institutions. It is both a product of institutionalization and part of institutional struggle.

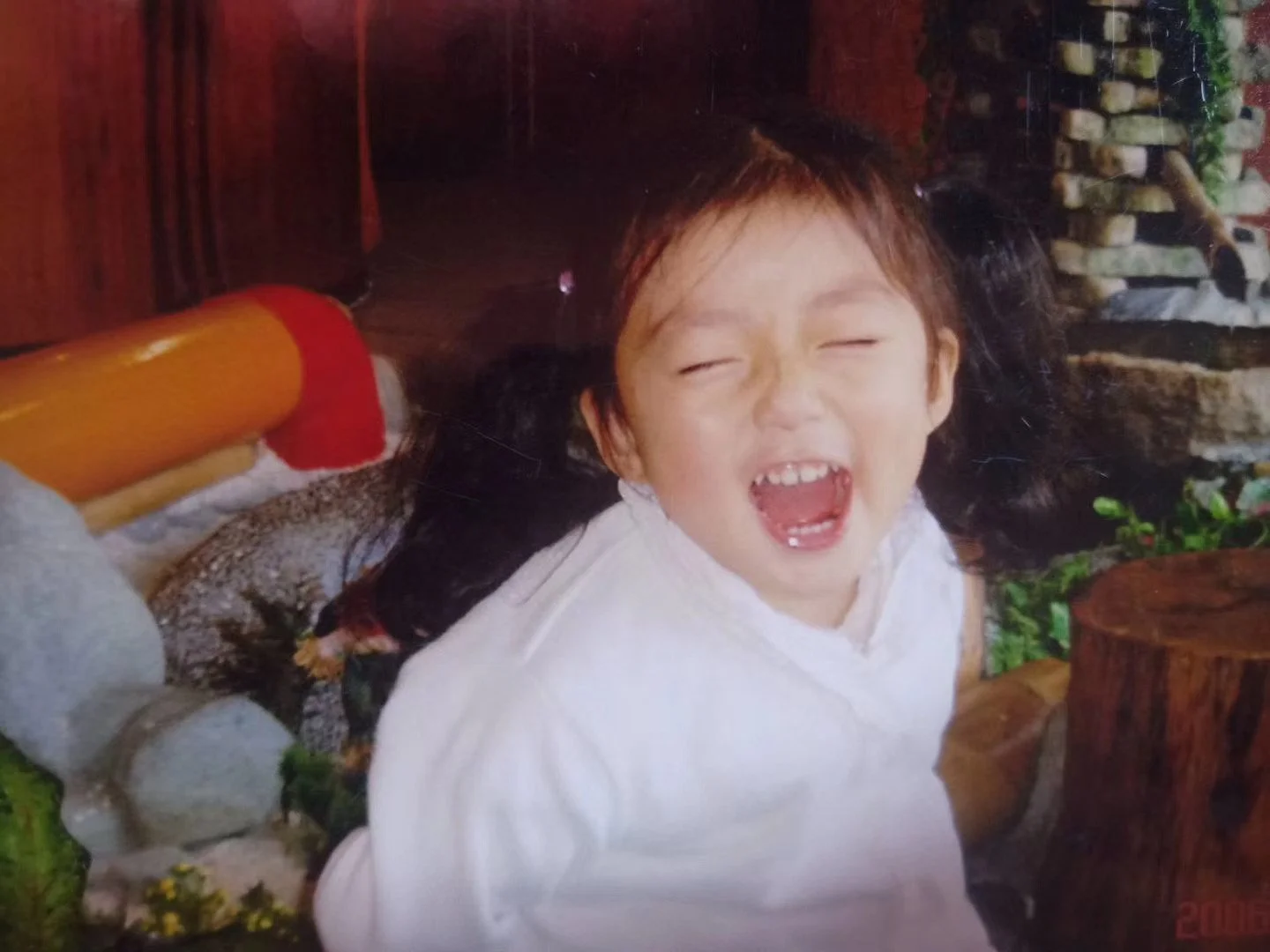

Photography is an ambivalent archive. It preserves memory while also distorting it.

As Trinh T Minh Ha argues in Documentary Is Not a Name, concepts are no less material than images or sounds. Images in archival art do not serve as neutral documents. They are shifting sites of interpretation. The documentary images I collected were originally visual records of family and cultural background. Much like the working method in Field Notes1, they were not produced through a predetermined artistic paradigm but rather through a diary-like impulse. Now, in retrospect, these materials have become fragments of a living archive. If the material is real, it becomes a record, but if it is fictional, it cannot be considered one. Therefore, to describe this process in language, the words must remain precise. The precision of language allows me to approach the structure of the archive I attempt to articulate.

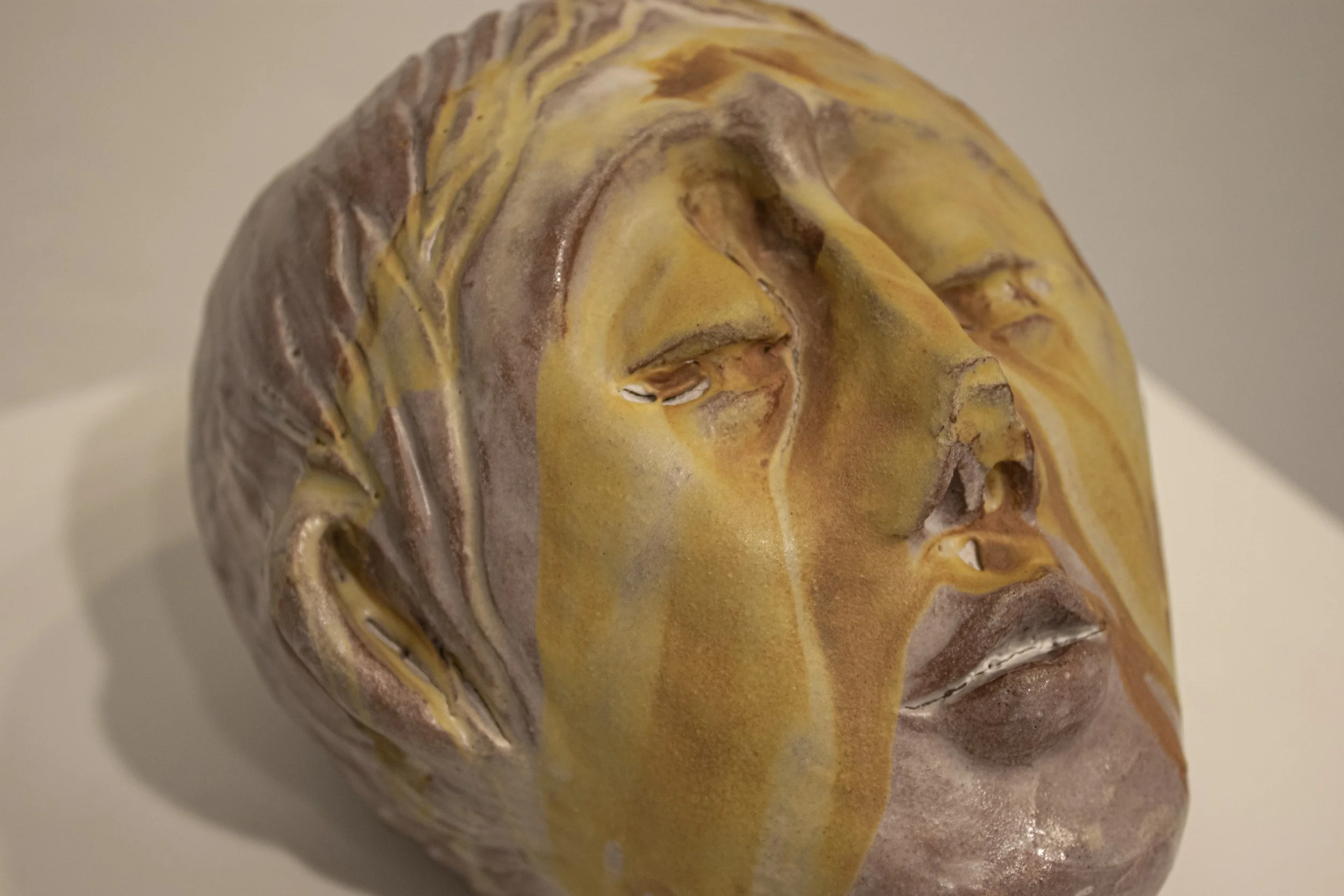

In previous practice, I have presented ceramics as ritualistic objects, imbuing them with significance beyond functional use. Many ceramic artists also employ personal rituals to infuse their work with spiritual meaning, shifting focus away from utilitarian purpose toward the experiential and ceremonial process of creation. This represents a state of coexistence between object and maker (Henley, 2002). When ceramics are embedded with personal emotion and memory, they demonstrate heightened vitality derived from an emotional language unique to the individual (Henley, 2002). This power from the psychological realm encourages artists to focus on sensory experience, to observe changes within material and self, and thereby to perceive the impermanence of life.

In March 2003, SARS broke out on a large scale in Taiwan, China. I was born in that spring under masks.

In my childhood memory, the impression of that small island where I was born was always vague. Instead, I remember the city where I finished China’s nine-year compulsory education—Hangzhou and my mother’s hometown—Shanghai. That southern island has always felt like it had a barrier for me. We clearly speak the same language, but it seems to carry a culture that is both strange and familiar.